Shipibo Designs and the Living Geometry of Icaros

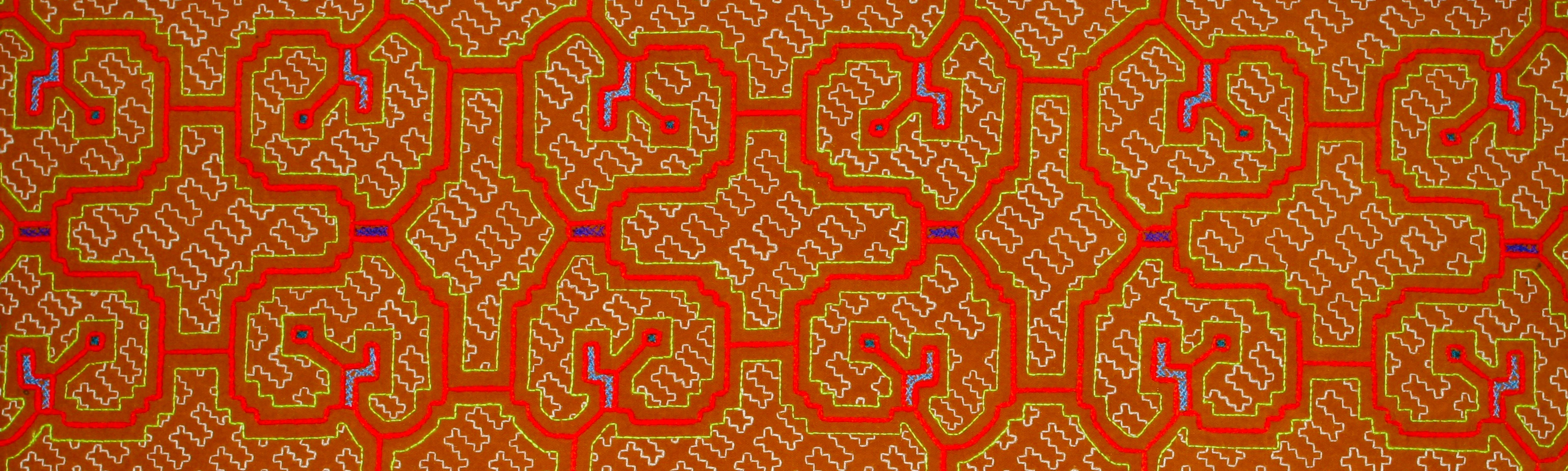

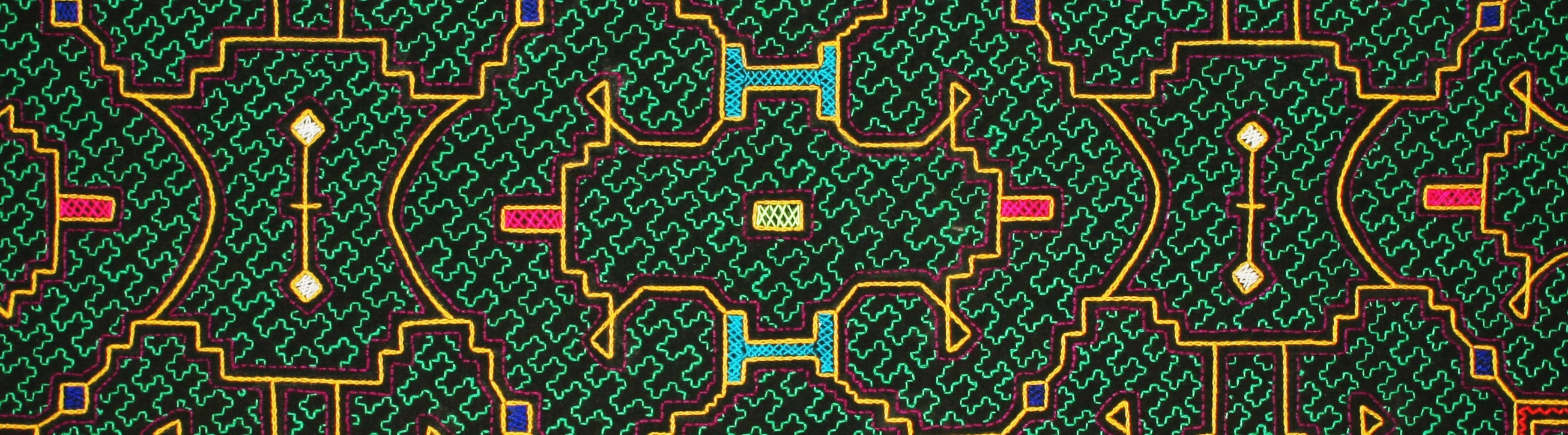

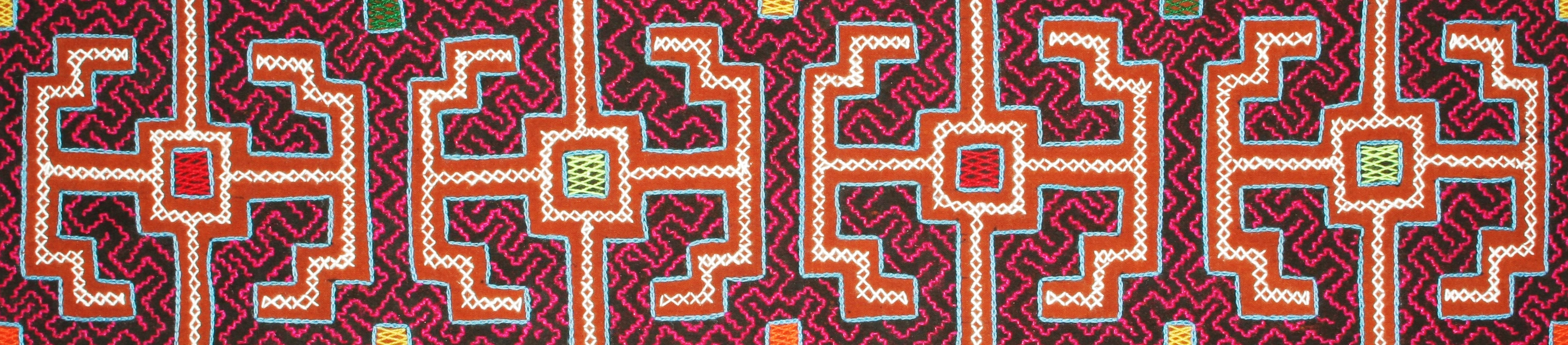

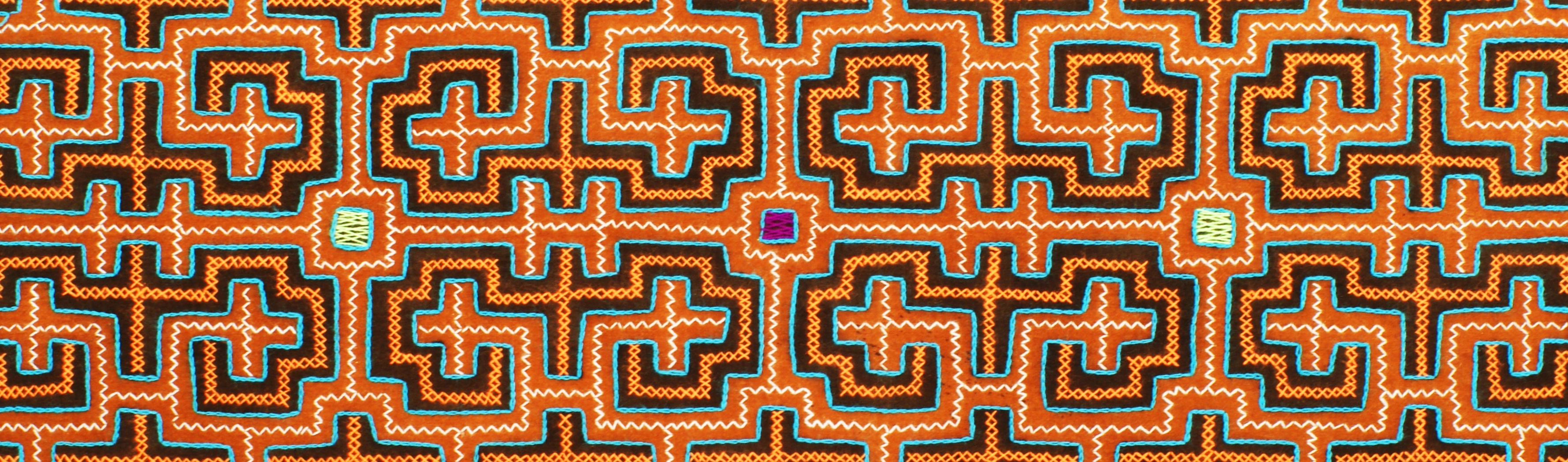

Shipibo designs are far more than decorative patterns. They belong to a sophisticated visual language known as "Kené", developed and preserved by the Shipibo-Konibo people of the Peruvian Amazon. This language is inseparable from the sacred healing songs called "Icaros", which are central to Shipibo medicine, cosmology, and ceremonial life. Together, sound and pattern express an ordered understanding of reality in which music, vision, and form are not separate domains, but different expressions of the same underlying structure.

In many descriptions, Shipibo art is associated with synesthesia — the merging of sound, colour, and pattern into a unified sensory experience. While this term can be helpful as a modern analogy, within Shipibo understanding the relationship runs deeper. Icaros and Kené do not merely resemble one another; they arise from a shared cosmological knowledge in which order, harmony, and healing are understood as patterned phenomena.

Icaros, Vision, and Healing

Icaros are sacred songs used by Shipibo healers to guide, protect, cleanse, and restore. During healing ceremonies, the shaman sings to address imbalance within a person — physical, emotional, or energetic. These songs are not improvised melodies in a casual sense, nor are they symbolic poetry. They are precise tools, learned through long apprenticeship and often through visionary experience.

Within Shipibo cosmology, illness is frequently understood as a disturbance of order. Icaros function by re-establishing coherence. Healers describe their work not as adding something new, but as correcting, straightening, or re-aligning what has become disordered. In visionary states — particularly those associated with Ayahuasca — this order is often perceived as flowing lines, grids, or interwoven geometries, forms that closely resemble Kené designs.

Importantly, the healer is not “singing a pattern” in a literal or illustrative way. Rather, the song acts upon the energetic structure of the person, guiding it back into harmony. The visual perception of patterned order is a consequence of this process, not a diagram being transmitted.

Ayahuasca and the Visionary Dimension

Ayahuasca holds a central place in Shipibo healing practice and is closely linked to the development and refinement of icaros. Through Ayahuasca ceremonies, healers enter visionary states in which they encounter teachers, songs, and ordered structures that inform their work. Many healers describe learning Icaros directly through these experiences, receiving them as complete songs rather than composing them consciously.

In these visionary states, the perception of Kené-like geometries is common. These are not regarded as hallucinations, but as manifestations of the underlying order of the world — an order that can be perceived, worked with, and restored. Ayahuasca does not create this order; it reveals it, allowing the healer to interact with it more directly.

While Ayahuasca plays an important role in the training and practice of healers, it is essential to note that Shipibo culture does not reduce Kené or Icaros to Ayahuasca alone. The knowledge predates modern ceremonial contexts and exists as part of a broader cultural and cosmological system.

Kené: Pattern as Knowledge

Kené designs are traditionally created and transmitted by women, who are the primary custodians of this visual knowledge. The patterns appear on textiles, ceramics, beadwork, and ceremonial objects, and are learned through disciplined practice, memory, and lineage. Women do not embroider Kené by copying specific songs, nor do they need to participate in Ayahuasca ceremonies to access this knowledge.

Instead, Kené represents an inherited understanding of order — one that is taught, refined, and embodied over generations. The patterns are constructed according to internal logic, balance, and rhythm, and are recognised within the culture as correct or incorrect, harmonious or disturbed.

Traditionally, Kené designs are painted or embroidered in vivid colours, often including tones that respond strongly to ultraviolet light. Pigments were historically derived from organic materials such as plants, bark, seeds, clays, and resins gathered from the forest. Each material carried practical, symbolic, and environmental significance.

Function Rather Than Symbol

Kené designs are not symbolic in a metaphorical or purely aesthetic sense. Within Shipibo understanding, they are functional. They organise space, support balance, and offer protection. When worn on the body, placed in a home, or used in ceremonial settings, they are understood to stabilise and maintain order.

For this reason, Kené can be described as a form of visual medicine. The pattern does not merely represent harmony; it holds it. In this way, Kené carries the presence of order long after a song has been sung or a ceremony has ended.

The Shipibo-Konibo People

The Shipibo-Konibo are an Indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon, primarily living along the Ucayali River and its tributaries. Their culture is known for its depth of medicinal knowledge, complex cosmology, and highly developed artistic traditions. Healing practices, plant medicine, music, and visual art are deeply interwoven aspects of daily and ceremonial life.

Despite centuries of external pressure, displacement, and cultural disruption, the Shipibo-Konibo have maintained a strong continuity of knowledge, particularly through oral transmission and embodied practice. Kené designs and icaros remain living traditions, not relics of the past.

To read a detailed article on the Shipibo-Konibo people, their history, and cultural resilience, click here.

A Living System of Transmission

Shipibo designs represent a living system of knowledge in which music, vision, healing, and craftsmanship are inseparable. Song and pattern are not translations of one another, but parallel expressions of the same ordered reality. One is heard, the other seen; one moves through breath, the other through line — both act.

In this context, art is not an object to be interpreted, nor a symbol to be decoded. It is a transmission: disciplined, functional, and alive.

Context Note / Disclaimer

When this article refers to healing or medicinal functions, it does so within the cultural and ceremonial understanding of the Shipibo-Konibo people. These descriptions are not intended as medical claims, nor as substitutes for modern healthcare. They are shared to provide insight into a living Indigenous knowledge system, not to prescribe or promote therapeutic use.

Copyright Notice

All written content in this article is protected under copyright law. Reproduction or distribution of the text, in whole or in part, without prior written permission is prohibited.

Photographs and images shown may represent Indigenous artwork or cultural expressions. These works are not claimed as original creations of this publication. Copyright, authorship, and cultural ownership remain with the Indigenous artists or communities from which they originate.