The Shipibo-Konibo People of the Peruvian Amazon

The Shipibo-Konibo are an Indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon, primarily living along the Ucayali River and its tributaries. They belong to the Panoan linguistic family and are known for a highly developed cultural system in which medicine, cosmology, music, visual art, and daily life form an integrated whole. Rather than existing as separate domains, these elements are understood as interconnected expressions of order, balance, and continuity.

Despite centuries of external pressure — including colonisation, missionary activity, displacement, and economic exploitation — the Shipibo-Konibo have maintained a strong cultural identity. Their knowledge systems remain active and adaptive, transmitted through oral tradition, embodied practice, and lived experience rather than written doctrine.

Territory and Way of Life

Shipibo-Konibo communities are traditionally river-based, with settlements organised along waterways that serve as transport routes, food sources, and spiritual reference points. Fishing, small-scale agriculture, hunting, and forest gathering form the basis of subsistence, supplemented today by varying degrees of engagement with regional markets.

Daily life is closely tied to the rhythms of the forest and river. Knowledge of plants, seasons, and animal behaviour is practical as well as ceremonial, and elders play a central role in transmitting this understanding to younger generations. While modern influences are present — including schooling, technology, and trade — these coexist with long-standing cultural frameworks rather than replacing them entirely.

Cosmology and Worldview

Shipibo cosmology understands the world as layered and ordered, inhabited by visible and invisible forces that interact continuously. Humans, animals, plants, rivers, and spirits are not sharply divided categories, but participants in a shared field of relations. Health, clarity, and stability arise when these relationships are in balance; disturbance occurs when order is disrupted.

Within this worldview, perception itself is a skill that can be trained and refined. Seeing, hearing, and sensing are not passive acts but forms of engagement with the world. This understanding underlies Shipibo approaches to medicine, art, and ritual.

Healing Traditions and Ayahuasca

Healing practices among the Shipibo-Konibo are rooted in plant knowledge, ceremonial discipline, and sound. Certain individuals undergo long apprenticeships to become healers, learning to work with songs (“Icaro”), plants, and ritual space. These practices are not framed as curing disease in a biomedical sense, but as restoring coherence where imbalance has arisen.

Ayahuasca plays a significant role in this context, particularly in the training and practice of healers. Through ceremonial use, practitioners enter altered states of perception in which they learn songs, encounter guiding forces, and refine their capacity to perceive order and disturbance. Ayahuasca is not viewed as a shortcut or universal remedy, but as a demanding teacher that requires preparation, discipline, and responsibility.

Importantly, Shipibo culture does not reduce healing knowledge to Ayahuasca alone. Many aspects of care and balance are maintained outside of ceremonial contexts and are embedded in everyday plant use, diet, and social conduct.

Music, Icaro, and the Use of Sound

“Icaro” refers to sacred songs used by Shipibo healers within ceremonial and healing contexts. These songs are learned over long periods of apprenticeship and are regarded as precise tools rather than expressive performances. Through sound, rhythm, breath, and intention, healers work to guide, protect, and re-align.

Rather than conveying meaning through lyrics, Icaro operate through structure, delivery, and resonance. Silence, posture, and attention are considered as important as the song itself. Sound is understood to act directly upon perception and space.

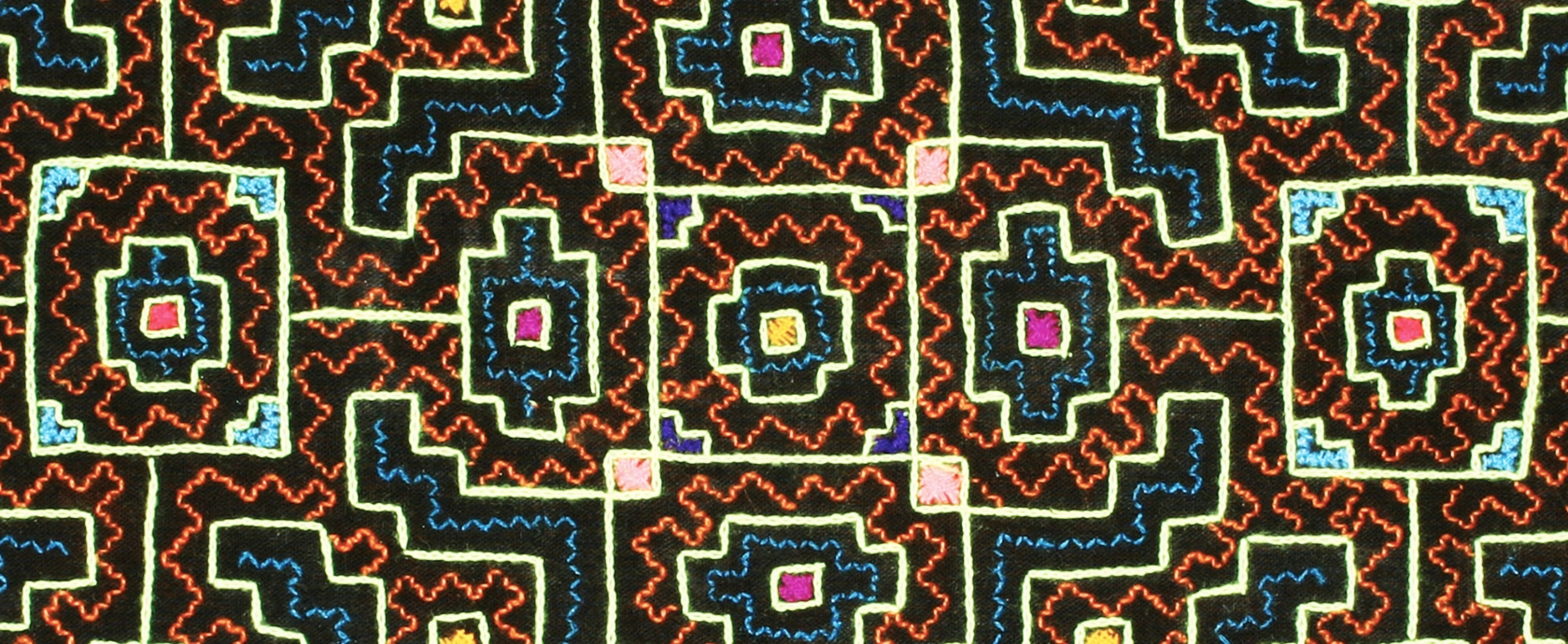

Shipibo Designs (Kené)

One of the most recognisable expressions of Shipibo culture is their intricate geometric designs, known as "Kené". These patterns appear on textiles, ceramics, beadwork, body paint, and ceremonial objects. Kené is not decorative in a superficial sense, but part of a complex visual language that reflects an ordered understanding of reality.

Kené exists in close relationship with Icaro, yet one is not a literal translation of the other. Both song and pattern are understood to arise from the same cosmological framework, expressing order through different sensory modes — sound and form. The creation and transmission of Kené is traditionally carried by women, who learn the internal logic of the patterns through disciplined practice and lineage.

To read a full, detailed article on Shipibo designs, Kené, and their relationship to song, vision, and cosmology, click here.

The Role of Sacred Tabaco and Mapacho

Sacred “Tabaco” holds an important but supportive role within Shipibo-Konibo ceremonial life. Unlike some Amazonian traditions where Tabaco stands at the centre of ritual practice, among the Shipibo it functions primarily as a plant of protection, grounding, and containment.

The form of Tabaco most commonly used is Mapacho — a strong, traditional Amazonian Tabaco variety. Mapacho is approached with restraint and seriousness, never as a casual substance. Its use is context-dependent and varies between lineages and healers.

Shipibo healers may work with Mapacho in several traditional ways:

- blown smoke (soplada) to cleanse, protect, or seal a person, object, or space

- grounding before or after ceremonies

- reinforcing focus and authority within ritual settings

Mapacho is often used alongside Ayahuasca ceremonies, not to induce visions, but to stabilise perception and maintain clear boundaries within the ceremonial space. It supports discipline and orientation rather than expansion.

While Tabaco may accompany healing work, it does not replace Icaro, nor does it function as a primary healing agent. Instead, it acts as a complementary ally, helping define where a process begins and ends.

It is important to note that although Rapé is a widespread Amazonian Tabaco preparation, it is not traditionally central to Shipibo practice in the way it is among several Brazilian tribes. Its presence among some contemporary Shipibo practitioners reflects intercultural exchange rather than ancestral custom.

To read a full, detailed article on Mapacho, click here.

Social Structure and Knowledge Transmission

Shipibo knowledge is transmitted primarily through lived practice rather than formal instruction. Children learn by observing, assisting, and gradually participating in daily tasks and ceremonies. Storytelling, repetition, and embodied example play a central role, as does the authority of elders.

Gender roles are complementary rather than hierarchical. While certain ceremonial functions are gender-specific, both men and women are considered essential carriers of knowledge. Healers, artisans, gardeners, and elders each hold distinct responsibilities within the community.

Contemporary Challenges and Continuity

Today, Shipibo-Konibo communities face ongoing challenges, including land pressure, deforestation, cultural appropriation, and economic marginalisation. At the same time, there is strong internal momentum toward cultural preservation and self-determination. Shipibo artists, healers, and leaders increasingly engage with the outside world on their own terms, asserting authorship, lineage, and continuity.

Kené designs, Icaro, plant knowledge, and ceremonial discipline remain living practices — not relics of the past. They continue to evolve while retaining their internal coherence and cultural grounding.

A Living Culture

The Shipibo-Konibo people represent a living culture in which art, medicine, and worldview are inseparable. Their traditions are not belief systems to be adopted or imitated, but disciplined practices embedded in land, language, and community.

To engage with Shipibo culture responsibly is to recognise it as ongoing, complex, and self-determined — not as a resource to extract meaning from, but as a knowledge system with its own integrity.

Copyright Notice

All content, including this article, is protected under copyright law. Any unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of this material is prohibited. Duplication of this content, in whole or in part, without written consent, is a violation of copyright regulations.