Caboclo

Bridging Forest and City – The Living and Spiritual Lineage of Brazil’s Mestizo People

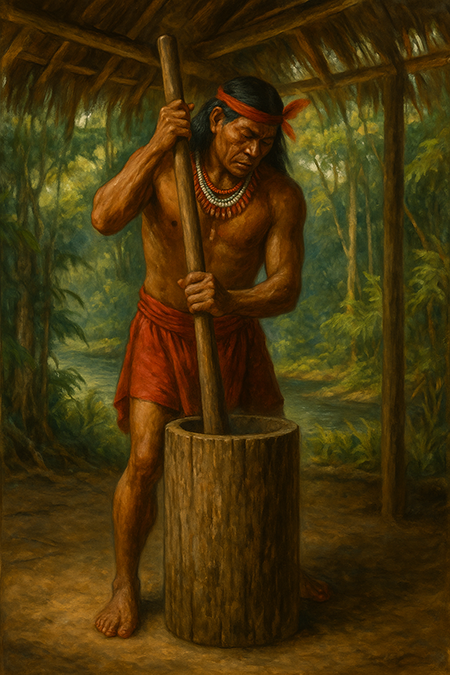

The term Caboclo carries several intertwined meanings within Brazilian culture. It describes both a people and a spirit — the descendants of Indigenous and European ancestry who live between the worlds of the forest and the town, and the sacred archetype of the forest warrior and healer that lives within the Afro-Brazilian spiritual lineages of Umbanda and Candomblé. Together, these meanings express a powerful continuity: the blending of Indigenous wisdom, rural resilience, and the protective energy of the forest.

Origins and Identity

The Caboclo people emerged through centuries of encounter and adaptation in the Amazon basin. Born from Indigenous families and European settlers — often Portuguese — they inhabit the riverbanks, forest margins, and small villages scattered throughout the interior of Brazil. The word Caboclo may derive from Tupi expressions such as caa-boc (“the one who comes from the forest”) or kari’boca (“the white man’s child”). In earlier centuries, the term was used to distinguish acculturated or mixed Indigenous people from those who resisted colonization. Today it refers to a living culture that carries deep ancestral roots in both forest and frontier.

Caboclo life has always been a negotiation between two worlds. While they participate in regional economies and trade, their worldview remains closely linked to the rhythms of the rivers and seasons. Their language, cuisine, and daily customs bear the marks of Indigenous ancestry, Christian symbolism, and Afro-Brazilian influence — forming a culture of remarkable adaptability.

Economy, Craft, and Daily Life

Caboclo livelihoods are diverse and practical, deeply tied to the environment. Many families sustain themselves through small-scale agriculture, fishing, rubber tapping, and the collection of forest products such as Brazil nuts, fruits, and medicinal plants. They are skilled in working with natural materials — crafting tools, baskets, canoes, and herbal remedies from their surroundings.

In modern times, some Caboclo artisans have transformed this heritage into sustainable craftsmanship and small-scale industries. One example is Caboclo Brasil, a workshop producing handmade leather shoes using traditional methods and natural materials — a contemporary expression of forest craftsmanship adapted for modern life. In other regions, Caboclo communities grow coffee, produce local honey, and trade natural extracts, maintaining a delicate balance between subsistence and small commerce. Their crafts and livelihoods remain expressions of coexistence with the forest — practical, humble, and self-reliant.

The Caboclo and the Medicine of Rapé

In the world of sacred plants, the Caboclo have become a bridge between traditional Indigenous makers and the broader public who seek connection with Amazonian medicines. For generations, Caboclo families have learned the preparation of Rapé and other plant-based tools through kinship or apprenticeship with tribal healers (pajés). When displacement, migration, or loss of land disrupted Indigenous continuity, it was often the Caboclo who carried the knowledge forward — collecting ashes, cultivating Tabaco, and preserving techniques of preparation.

Today, Caboclo artisans continue to play a vital role in the dissemination of Rapé beyond tribal territories. Some maintain direct collaboration with Indigenous tribes, exchanging materials and blessings, while others work independently but with sincere devotion. Their preparations may blend tribal recipes with accessible ingredients, keeping the ceremonial essence intact even as the medicine travels to urban and international contexts.

This role, however, demands sensitivity. As Rapé becomes more available commercially, the Caboclo stand at a threshold between tradition and market. The most conscious makers approach their craft as sacred stewardship rather than trade, recognizing that the true authenticity of Rapé lies not in the name of its maker but in the reverence, prayer, and integrity with which it is prepared.

The Caboclo as Spiritual Archetype

Beyond the Amazon’s riverbanks, Caboclo also names a class of spiritual entities central to Afro-Brazilian religions such as Umbanda and Candomblé. In these traditions, the Caboclo is not a mortal person but a guiding spirit — the embodiment of courage, purity, and the untamed wisdom of nature. These spirits are said to “descend” into mediums (pais de santo) during ceremony, taking the form of noble forest beings who offer advice, protection, and healing.

In Umbanda, the Caboclo represents the spirit of the forest — strong, direct, and compassionate. Alongside the Pretos-Velhos (old African spirits) and the Erês (child spirits), the Caboclos are regarded as pillars of the spiritual hierarchy. They speak through the voice of simplicity, reminding humanity of humility, honesty, and harmony with the earth.

In Candomblé, the Caboclo plays a parallel role: a messenger who conveys the will of the Orixás in Portuguese rather than Yoruba, making ancestral wisdom accessible to all. They bring comfort to the grieving, guidance to the lost, and prescribe symbolic offerings — fruits, roots, and sweets — often accompanied by Fumo de Rolo (rolled Tabaco) and honey. Tabaco is the key to their communication, an offering that links their presence to the living forest and to the sacred breath of creation.

Cultural Continuity and Symbolism

Through both their human and spiritual forms, the Caboclos symbolize the meeting of nature and civilization, ancestry and adaptation. They remind us that the forest is not only a place of survival but a teacher — that the medicine of the plants continues to flow through those who walk humbly between worlds.

Their role in Rapé culture reflects this same principle: continuity through transformation. Whether preparing blends in a remote river village or invoking the forest spirit in an urban temple, the Caboclo expresses an ancient truth — that the relationship between people and the forest is reciprocal. To give offerings, to prepare medicine, or to blow Rapé into the nostrils of another is to affirm that all wisdom, all healing, and all guidance ultimately arise from the same source: the living breath of the earth.

Copyright Notice

All content, including this article, is protected under copyright law. Any unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of this material is prohibited. Duplication of this content, in whole or in part, without written consent, is a violation of copyright regulations.